Share on

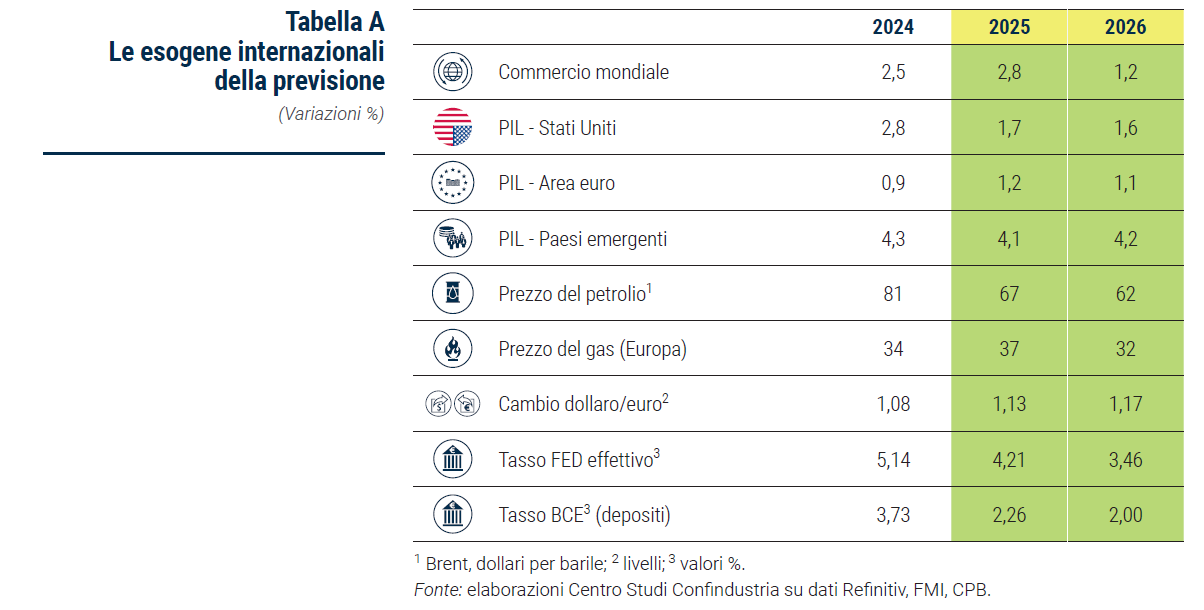

1. The international scenario is weakened: rising tariff and non-tariff barriers weigh on trade prospects. Barriers to free international trade do not only come from US trade policy, but affect most countries: in the first eight months of 2025, protectionist measures launched around the world are at their highest. Global trade accelerated in Q1 2025 due to the so-called frontloading of US sales, i.e. the anticipation of tariffs introduced in April on almost all incoming goods; conversely, there was a sharp downward correction in Q2. In the scenario of the Centro Studi Confindustria (CSC), world trade will grow by +2.8% on average in 2025, but then slow down to +1.2% in 2026 (Table A): compared to the April report, the dynamics are revised upwards in the current year due to the mechanical effect of frontloading at the beginning of the year, but very much downwards in the coming year. In addition, significant downside risks remain, mainly related to a possible escalation of economic and political conflict between large blocs of countries worldwide.

A brake on world growth also comes from theuncertainty which remains at a very high level: the index of global economic policy uncertainty peaked in April 2025, declining in the summer, but remaining at the same level as in 2020, during the pandemic. The biggest contributor to this uncertainty comes from US trade policy: despite the fact that agreements have been reached with America's main trading partners, which has helped to clarify the new tariff situation with the world's largest buyer, there remains both the risk of further changes and the lack of agreement with some countries. This uncertain scenario makes financial markets more volatile, penalises investment decisions, especially international ones, and pushes to reconfigure global supply chains.

The economy most damaged by the duties is precisely that of the United States. Economic indicators still seem to suggest weakness in the second half of this year. Monetary policy is somewhat less restrictive, but the recent cut in official rates will only make its positive effects on investments felt in a few quarters. In addition, inflation expectations suggest an acceleration of prices and put further rate cuts and even more robust consumption growth at risk. As a result of these factors, the US economy is assumed to maintain a much more moderate pace of growth than in 2024, only recovering some momentum in late 2026. In the CSC scenario, GDP growth is expected to slow to +1.7% in 2025 and +1.6% in 2026, from +2.8% in 2024. It is revised downwards despite a higher-than-expected rebound in Q2 2025, after a decline at the beginning of the year, a swing attributable to the introduction of tariffs.

Despite the deterioration of the international environment due to protectionist policies, the emerging economies will continue to boast sustained growth rates, in aggregate at +4.1% in 2025 and +4.2% in 2026, albeit down from the April CSC forecast. This is the result of a reconfiguration in trade and investment, which is increasingly shifting towards the Asian centre of gravity, driven mainly by China (which continues to expand at rates close to +5.0%) and also by India (which registers the highest growth among the top 20 emerging economies). Russia, affected by Western sanctions but supported by the strengthening of economic relations with Beijing, is expected to stabilise on more moderate, but still positive, growth rates. In general, in the emerging countries, inflation continues to fall, exchange rates in several countries are under pressure, trade balances are worsening, and fiscal policies remain expansionary.

I US duties towards the rest of the world are reshaping the geography of global trade, particularly trade with Europe. The new regime between the two sides of the Atlantic has acquired fairly definite connotations: zero tariffs on EU purchases of US industrial products; tariffs at 15% on most US imports from the EU (including cars, non-generic drugs, semiconductors); US tariffs at zero or almost zero on other EU products in strategic sectors (aircraft, generic drugs, some natural resources); duties at 50% on steel and aluminium remain. The agreement includes commitments on the European side of uncertain outcome, because they invest areas of competence of national authorities and also private companies: purchase of energy goods, AI chips and military equipment from the US; direct investments in strategic US sectors. These duties, together with the strong euro against the dollar (which they themselves have brought about), greatly penalise the price competitiveness of European goods in the US, especially with respect to US domestic production, and also in the rest of the world. After the pre-Thanksgiving frontloading, US imports from the EU fell by -8.7% year-on-year in June-July; those from China by -39.9% (in line with the weight of tariff revenues by country of origin). In the long run, there is a strong incentive to relocate some production to the US market: the risk for European industry is to lose vital parts of the production fabric.

2. The European economy suffers from the worsening global scenario: GDP growth of theEurozone over the forecast horizon is lower than in the US, reaching +1.2% in 2025 and +1.1% in 2026. For 2025, however, this is an acceleration after the +0.9% in 2024, but it is mainly explained by the strong expansion in Q1, spiked by the anomalous figure for Ireland. In the area, investment has been very volatile so far, while consumption is more stable but at a weak pace. Net exports benefited from the frontloading effect at the beginning of the year, but then suffered a negative rebound in the spring. This fluctuating trend was also reflected in the figures for European industry, which on the whole showed some positive signs, but largely to meet demand from the US in anticipation of tariffs in early 2025. And without having resolved structural difficulties, such as the disadvantage in energy costs compared to the US. Looking ahead, economic indicators do not promise a solid rebound of the European economy. The trend in the near future is linked to the expected restart of investments, which have not yet taken a clear direction and which could benefit in 2026 from lower rates and the pull of growth sectors, such as defence.

Crucial will be the trajectory on which the area's leading economy manages to position itself. After two years of mild recession in 2023-2024, the GDP of the Germany recorded an essentially flat first half of 2025. In particular, the decline in Q2 was not only due to the frontloading effect on exports and imports, as investments also fell again. The German economy, therefore, is not yet out of the crisis, but thanks to the positive effects of recent reforms it is expected to gradually strengthen, to return to growth from 2026 at rates above +1.0%. In fact, the government recently approved a constitutional amendment to the 'debt brake' and launched a structural reform programme to facilitate investment in infrastructure and defence spending. In addition, a EUR 500 billion fund was created for 12 years, also excluded from the debt brake, to improve Germany's infrastructure, including railways, roads, and hospitals. Over the summer, signs of a recovery, albeit slow, began to be seen in many indicators, including industrial production. The consolidation of these signs will depend on when and how the German government manages to implement the massive investment plan.

Meanwhile, the ECB completed the rate cutIt held them steady at 2.00% in September 2025, after a rapid run of eight cuts of a quarter point each from June 2024 to June 2025, starting from a peak of 4.00%: monetary easing in the euro area amounted to -2.00 points. The ECB can count on stable inflation in recent months, close to the target of +2.0%, and inflation expectations in the area are also stable, although several risks remain in the scenario, particularly on commodity prices. The monetary stance, thanks to the cuts, is no longer restrictive and funding conditions in the banking channel have become more favourable. Overall, the official ECB documents give the message that in the absence of further shocks, the monetary policy correction is sufficient for the time being. Financial market expectations are consistent with firm rates over the forecast horizon. Therefore, the CSC scenario assumes that there will be no further rate cuts, although there remains a positive probability that the ECB will decide instead to resume the path of cuts in the coming months to support weak European growth.

Regarding the cost of energy, the news is partly positive. The Brent oil price shows a slightly declining trend, albeit with significant fluctuations reflecting the alternating news about the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. Recent values are in line with the historical equilibrium values for the world market (USD 60-70), at the end of the long adjustment phase of the physical market after 2022. The conservative assumption of the CSC scenario is that Brent crude will drop to an average of $67 in 2025 (from $81 in 2024) and to $62 in 2026. The price of gas in Europe also fell, but less: 32 euro/mwh in August 2025, down from a high of 50 euro touched in February. Fears of shortages on gas volumes remain moderate and markets now expect prices to remain close to current values. However, European gas prices remain very high compared to pre-pandemic levels (EUR 14 in 2019), due to the transition implemented in Europe since 2022 and now completed, to liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is more expensive, and to alternative supplier countries to Russia, which are politically unstable. The price in Europe also remains much higher than in the US, about three times higher, as the US market price is kept low by the boom in shale gas extraction.

For Europe, the conclusion of trade agreements is an essential tool to counter the fragmentation of international trade. The free trade treaty between the EU and Mercosur has come to an end, pending political ratification. The agreement represents an asymmetric tariff liberalisation: the EU grants limited access to South American agricultural goods linked to food safety standards, while it obtains a wide opening in the industrial and service sectors. Mercosur (especially Brazil and Argentina) also plays a crucial role as a supplier to Europe of critical raw materials, which are crucial for the digital and energy transition. The free trade area that will be created will consist of more than 700 million people, producing about one fifth of global GDP: almost 40% more in population than the USMCA (United States, Mexico and Canada), 10% less in GDP. All this will favour a significant expansion of EU exports, also strengthening existing production links. Thus, market shares in the Mercosur countries are expected to recover for the EU countries, which have just overtaken China as the leading trading partner. Today, the top two European countries by market share in Mercosur are Germany and Italy, mainly as suppliers of capital goods. These two countries are the European economies that will benefit most from the lowering of tariffs with Mercosur, as they have a product specialisation in the sectors where the reduction in tariff rates will be strongest.

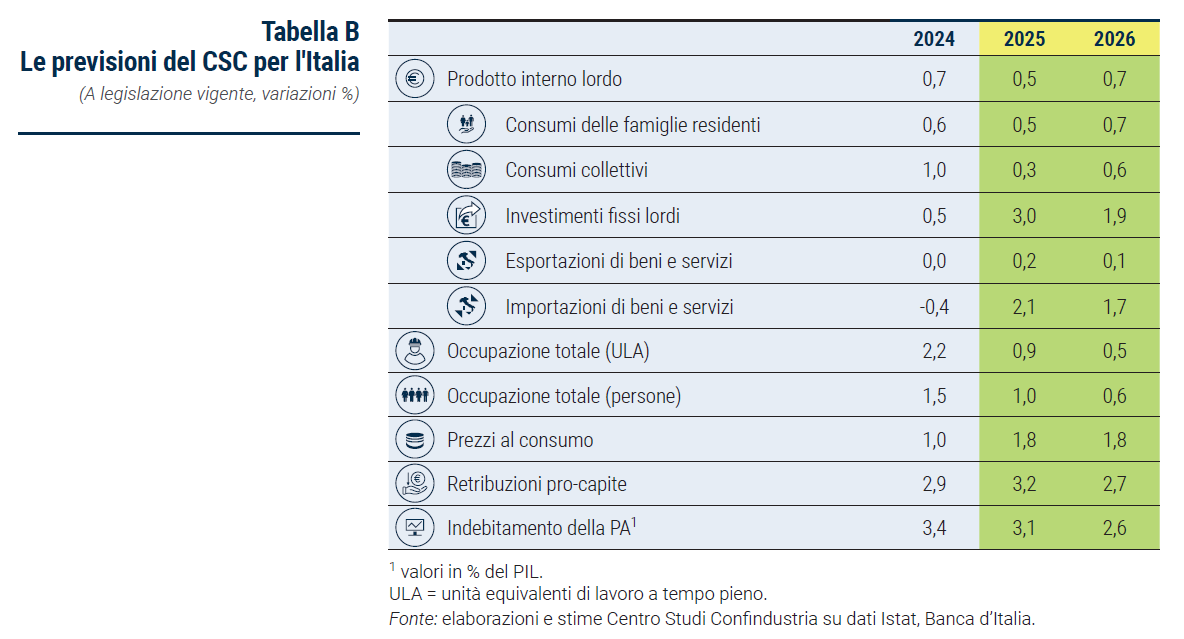

3. Penalised by the difficult global and European context, the growth in Italy will remain low over the forecast horizon (Table B): according to the CSC scenario, there will be an annual increase in GDP of just +0.5% in 2025, 0.1 points lower than projected in the April scenario. Italian growth is expected to accelerate only slightly in 2026, to +0.7%, returning to the pace of 2024. The economy's annual momentum is held back in particular by the setback in Q2 2025, when Italian GDP declined by 0.1%, due to the fall in exports. The weak GDP dynamics, both in the average of 2025 and in 2026, will be supported mainly by investments, to a lesser extent by household consumption, while net exports will contribute negatively.

The weakest component of demand in Italy is the exports. In the CSC scenario, the growth of exports of goods and services, which was already very weak in 2023-2024, will be close to zero in 2025-2026; in particular, sales of goods are expected to decline. Imports, on the other hand, will be on the rise and, as a result, net exports will make a very negative contribution to the change in GDP. The export profile is significantly revised downwards compared to the April report, due to the jump in US tariff barriers on European products and the escalation of global geopolitical tensions. Goods exports are also losing ground compared to world trade, because demand in Europe (the main destination for Italian products) is still weak and because the strong euro is penalising the competitiveness of products throughout the Eurozone. The outlook is not good, as European industrial activity is expected to recover only gradually and protectionist and geopolitical brakes appear to be lasting. On the positive side, the ratification of the EU-Mercosur agreement would open up important outlet markets, partially offsetting the barriers in the US market.

Conversely, the most robust demand component in Italy is the fixed investments. After slowing down in 2024 (+0.5%), their momentum strengthened again between the end of last year and the first half of 2025. They are expected to remain expanding in the second half of this year (+3.0% on average) and slow down next year (+1.9%). In addition to benefiting from the no longer restrictive monetary policy, which will have a mitigated impact next year, investment has been effectively stimulated by fiscal incentives. Those in residential construction, which fell in 2024 but rebounded this year, are being supported by Ecobonus and Bonus Ristrutturazioni, albeit depressed compared to the past; those in machinery and equipment and intangibles, by Transition 4.0 and, after the latest simplifications, also by Transition 5.0; the NRP is driving investment in non-residential buildings, a pull that will fade in 2026 due to the mid-year end of the Plan.

I household consumption in the first half of 2025, especially demand for goods, while expenditure on services grew at a moderate pace. In the CSC's forecast scenario, consumption is expected to grow modestly also in the coming quarters, reaching +0.5% in the average of 2025 and +0.7% in 2026. The main cause of this weak momentum is the high propensity to save, caused by the abnormal uncertainty, which is dampening the positive effect of household income expansion this year; for next year, the modest assumed decline in the savings rate, on the other hand, leaves some room for consumption expansion. Households, therefore, show structurally more cautious consumption and saving habits, given the high risks of the scenario and because they are still reckoning with the price rises of the last few years, as the price level has remained permanently higher. Another change in the habits of Italian households is the high propensity to invest, which relates to expenditure on building renovations: it has fallen only slightly compared to the peaks reached with the Superbonus. There are various reasons for this: families have become familiar with the tax tool of deductions; in the climate of uncertainty, the house has become even more of a 'refuge asset' and renovations consolidate the value of real estate assets; the boom in short rentals, especially for tourism purposes in large cities, encourages investment in renovations of second homes.

4. On the supply side, the Italian industryAfter a good restart in Q1 2025 in terms of production, it slowed down already in Q2. These barely positive figures come after the sharp drop in production in 2023-2024, which brought the industry back below pre-pandemic levels. In 2025, strong uncertainty also pervades the economic indicators, which give mixed signals, including a marginal upturn in orders from within manufacturing companies and the PMI finally returning to the expansionary zone. Signs of slow and partial recovery are coming from the automotive sector, a key sector of Italian manufacturing, which is showing a turnaround (upward) in production from the beginning of 2025, although this is insufficient to make up for the slump of the previous two years. In the CSC scenario, elaborated in terms of added value, the industry is expected to recover in 2025 (+1.0%), but slow down next year (+0.4%), when the effects of investment incentives will wear off and the positive impact of lower rates will fade.

In the first half of 2025, the total added value in Italy grew thanks mainly to the good performance of the constructions. In fact, those of the residential type, which had been strongly affected in 2024 by the reduction of incentives, experienced an upward trend reversal between the end of last year and the first half of 2025. Non-housing construction has been booming for two years now and should continue to benefit from NRP resources and cheaper bank loans. The overall value added of the construction sector will further improve in the second half of this year, growing by +3.1% on average in 2025, before slowing down to +1.4% in 2026.

The sector of private servicesIn contrast, it remained practically static in the first half of 2025. The most recent economic information, relating to Q3, does not yet indicate a significant recovery in the sector, although tourist arrivals in Italy were up by +4.6% per year in July and business confidence in services has strengthened. The value added of services, therefore, is expected to maintain a slow pace of growth in the second half of 2025 and early 2026, before gaining momentum in the second half of next year, thanks to lower uncertainty and therefore a lower propensity to save, the delayed effect of the increase in real disposable income and more favourable rates on consumer credit. In the CSC scenario, the sector's value added would grow marginally in 2025 and more robustly in 2026 (+0.6%).

In 2025 employment continues to grow faster than GDP (+0.9% ALUs, already largely achieved in Q2), but will slow down in 2026 (+0.5%), leading to an initial recovery in labour productivity. Industry in the narrow sense, after a phenomenon of 'employment without growth' during the energy crisis and until the first half of 2025, is the sector where labour productivity is most compressed (-4.7% the added value per hour worked in Q2 2025 compared to Q4 2019). In the forecasts of Centro Studi Confindustria, the weak advance in industrial activity expected in the second half of the year will, however, be accompanied by substantial stability in labour input, which will grow at a more moderate pace than value added even in 2026. The construction sector, in stark contrast to the industrial sector, is characterised by large gains in labour productivity compared to pre-pandemic, expected to remain at high levels in the forecast scenario.

The prolonged and extensive post-pandemic recovery has reduced the unemployment rate from 10.2% in April 2021 to 5.9% in July 2025, the lowest since 2007; the rate is expected to average 6.0% in 2025 and 5.8% in 2026.

The dynamics of salaries per capita in the Italian economy as a whole accelerated to +2.9% in 2024 (from +1.8% in 2023) and to +3.1% in the first half of 2025, a pace at which it is expected to remain on average this year (+3.2%), decelerating only slightly next year (+2.7%). Thanks to wage dynamics remaining above inflation, the slow recovery of real wages will continue, advancing by +2.3% cumulatively over the two-year period 2025-2026. The recovery started already during 2023, driven by the private sector, where real wages per AWU in Q2 2025 recovered almost 40% of the large loss in purchasing power generated by the energy crisis (-5.3% over Q1 2021, from a low of -8.5% in Q4 2022). In the public sector, which accounts for about a quarter of the total wage bill, real wages per capita fell even further with the price surge in 2022 and were still 9.4 percentage points lower in spring 2025.

Inflation in Italy is fairly stable, thanks to the fall in energy prices, which is offsetting the acceleration in food prices. Looking ahead, it is expected to remain around current values, averaging +1.8% both this year and in 2026, i.e. at the levels at which core inflation has recently settled. This favourable scenario is based on energy prices in Europe continuing their downward trend, while still remaining high, and on a firm exchange rate, implying appreciation of the euro against the dollar. As a result of moderate sales price developments and rising costs, the mark-up in manufacturing has been eroding sharply since 2024 and is only stabilising in 2025. The inflation differential with the Eurozone persists: in the Area it is higher than in Italy by +0.5 percentage points; this differential arises on the prices of services and industrial goods, for which European inflation is stably higher. Therefore, in terms of Italian inflation, the interest rate cut could be deeper.

The credit channel has broken down, with the annual dynamics of bank loans to Italian companies finally returned to positive territory in recent months (+0.7% to July 2025). This is thanks to the rapid phase of ECB rate cuts, which ended in June 2025 and induced a loosening of credit supply, in the form of a reduction in the rates paid by businesses: the cost of credit fully incorporated the cuts, with the rate on new transactions at 3.50%, from a peak of 5.59% in November 2023, an overall drop of more than 2.0 points. These lower rates also allowed for an upturn in demand for credit from businesses, in particular requests for credit to finance fixed investments. Over the forecast horizon, interest rates are expected to stop at current levels, which are 'neutral', i.e. not as high as in 2024, but not as low in historical perspective either. Therefore, some companies may still face difficulties in terms of high debt burdens, although the annual dynamics of corporate lending is expected to strengthen, supporting investment.

In the CSC scenario, the public deficit is falling, below the EU threshold of 3.0% of GDP in 2026, creating the conditions for an exit from the excessive deficit procedure. The debt, however, continues to rise, due to interest expenditure and the additional accounting effects of the Superbonus.

5. The anaemic GDP growth expected this year and next makes it necessary to moving Italyby intervening with the most effective levers available, including by releasing financial wealth from its parking in unproductive bank deposits. The very positive impact of the NRP, which is already at work but will be completed in the early months of next year, must be accompanied by a budget manoeuvre that wisely continues along the path of stimulating productive investments. Investments are necessary to relaunch the country's growth and incentives can work effectively to stimulate them, including in the south of Italy, as we have seen in recent years.

The implementation of the NRP, which includes public investments, reforms, incentives, will have a very positive impact on GDP growth in the two-year forecast period: between 2025 and 2026 the planned resources amount to about 130 billion. The assumption of the CSC scenario is that half of the available resources, about 65 billion, will be spent; this includes about 11 billion, equal to half of the unspent resources in 2024, which slip to 2026. According to a CSC simulation, the positive effect of the PNRR on GDP is estimated at +0.8% in 2025 and +0.6% in 2026, compared with the change in the baseline scenario (+1.4% cumulated over the two years). This means that the dynamics of Italian GDP in the absence of PNRR would be -0.3% in 2025 and +0.1% in 2026 (-0.2% in the two-year period): there would be no growth, but stagnation.

Ex-post evaluation analyses say that the investment incentives in capital goods 4.0 have contributed to the surge in investment recently observed in Italy. This upswing, however, is not yet sufficient to restore equity to pre-financial crisis levels of 2008. Investments in tangible and intangible assets with high technological and digital content are essential, given the large gap that Italy still has in advanced technologies: the propensity to invest in these assets has grown in Italy, but remains lower than in other advanced economies. Tax incentives for 4.0 investments will largely end at the end of 2025: it is necessary to go back to designing incentives that have the potential to make the necessary leap for Italy. On the basis of existing ex-post evaluation analyses, it is estimated that the incentives under the Transition 4.0 Plan provided between 2020 and 2022 increased the rate of investment: more than doubled for micro-enterprises, almost doubled for small enterprises, increased by about 35-45% for medium-sized enterprises, and by 20-25% for large enterprises. CSC calculations show that the tax credit on investments in tangible assets 4.0 in the three-year period 2020-2022, by stimulating 'additional' investments, has allowed the State a significant revenue recovery: the measure, costing 20.3 billion, has paid for itself for almost half of the expenditure (48.6%). Considering all the main tax relief measures on capital goods (net of means of transport) and intellectual property products (not only 4.0), between 2016 and 2024 they would have repaid themselves for about a quarter (23.5%) of the public resources spent (74.6 billion).

A crucial role in accelerating investment can be played by the financial wealth of Italian households. This wealth is growing rapidly and has reached enormous values, amounting to over EUR 6,000 billion in 2024, fuelled primarily by the high savings of recent years. In particular, household bank deposits in Italy have reached over 1,500 billion, about a quarter of the total. Mobilising even a small part of the total wealth of Italian households could free up substantial resources to finance new productive investments in the country: for example, shifting just 1.0% from deposits to bonds and shares issued by Italian companies could translate into the financing of 15 billion new investments. For this, well-constructed policy measures are needed to induce households and large financial intermediaries (such as pension funds, insurance companies, mutual funds) to move resources towards instruments issued by our companies. It should be emphasised that these resources could also be usefully employed to finance infrastructure of national interest, investments in health and education, creating a more favourable environment for growth.

After decades of divergence from the Centre North, from 2020 GDP growth in the southern regions exceeded that of the rest of the country: between 2020 and 2023, +7.1% cumulative, more than the North (+5.1%) and the Centre (+2.8%). Without the South, growth would have been lower by half a cumulative point over this period. From pre-pandemic to 2024, more than 40% of the increase in employment in Italy was concentrated in the South: 355 thousand, out of 823 thousand. Exports from the South grew from 2019 to 2024 by about 30% and by 2022 exceeded the dynamic of those from the Centre North. This is due to several factors. First, the higher growth of investments in the South, also thanks to the contribution of the ZES tax credit for capital goods and despite the annual financing horizon that remains an important element of weakness. Second, a very positive contribution comes from the PNRR: 60.7 billion dedicated to the South, where 108 thousand projects out of 298 thousand are located (36%); in order to optimise their impact, it is important to solve the area's structural problems, such as slower payment speeds and delays in the completion of works. Thirdly, a crucial contribution comes from the 'ZES Unica per il Sud' (Single Economic Zone for the South), operational since August 2024, an enabling factor for private investment that has allowed for important simplifications: there are already around 800 'Autorizzazioni Uniche' (Single Authorisations); the 'Decontribuzione Sud' tool, which is waiting to be renewed, is also important. Finally, cohesion policy (national and European) remains a fundamental instrument for the Mezzogiorno, even though the administrative capacity of various territories needs to be strengthened. If we add to the PNRR the resources of the SIE funds, which allocate 48 billion to the South, and those of the FSC, which bring 47 billion, we arrive at a total of about 177 billion over a multi-year horizon.